Written by Dr. Katherine E. Arden and Dr. Ian M. Mackay

Help wanted.

On August 8th, this epidemic was labelled by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). The time for help to arrive and be effective is now. Before 70% of the predicted hundreds of thousands of cases to become infected by this variant of Zaire ebolavirus die. Money is required, and Australia has now donated eight million dollars. Three weeks ago a one billion dollar cost was forecast; a ten-fold increase in a month.[6] But what is really needed urgently are people. People to create beds through the building of treatment facilities, people to staff those facilities to provide the best supportive care possible under the circumstances, people to be trained to safely care for the sick and dying and to trains others, people to track cases, people to help educate family members in how to care for a sick loved one, people to help the psychologically traumatised try and deal with the loss of their children, their parents, siblings, cousins and friends. People are what’s needed. The United Nations (UN), which includes Australia, unanimously adopted Resolution 2177(2014) on the 18th of September within which it provided some instructions to member states. One of those is:

“8. Urges Member States, as well as bilateral partners and multilateral organizations, including the AU, ECOWAS, and European Union, to mobilize and provide immediately technical expertise and additional medical capacity, including for rapid diagnosis and training of health workers at the national and international level, to the affected countries, and those providing assistance to the affected countries, and to continue to exchange expertise, lessons learned and best practices, as well as to maximize synergies to respond effectively and immediately to the Ebola outbreak, to provide essential resources, supplies and coordinated assistance to the affected countries and implementing partners and calls on all relevant actors to cooperate closely with the Secretary-General on response assistance efforts;”Australian Prime Minster Tony Abbott noted to the UN that “We were one of the first countries to arrive with help in Japan after the 2011 earthquake; and in the Philippines after the 2013 typhoon.”[5] Why haven’t we arrived in West Africa yet?

Australian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop said on 29th of September, that Australia has not been specifically asked by the WHO to provide healthcare professionals to help.[2] But we a member state of the UN and the WHO is the United Nations’ public health arm. In that article the Minister was quoted as saying that we were unable to repatriate infected Australians safely, with this being an integral reason behind our limited response to the Resolution.

Lightbulb Moment.

Until the Foreign Minister’s comment, the importance of the US concept of building a smaller, healthcare worker-specific treatment facility in West Africa was perhaps lost on the two of us. Such an elitist construction looked bad to the people of the region and, without sufficient background, to others outside it. However, if such a facility reduces or removes the need to spend tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars per person [3] to send them home for treatment, then it seems like a brilliant plan. That money could be better spent, and the added healthcare should help attract more international healthcare workers to the region. In fact, why doesn’t Australia assemble the components and airlift a similar facility, flat-packed, to one of the regions in need of our help? This could be done in a jiffy with Australian military precision. Once built, this facility may well remove the need to repatriate any Australian healthcare professional who may get infected. This may be a better and faster solution than us trying to use British or US facilities or doing a deal with them to evacuate our people.

A good global citizen.

Prime Minister Abbott noted “That is what you’d expect from a country such as Australia which always wants to be the best global citizen”.[4] We are currently not being the best global citizens that we could be.

Let’s not hide behind excuses. Do we want our national character to be stingy and afraid or strong, generous and willing to give a fair go to those in need? We pride ourselves on our innovative character. We can use this to find a way around problems, real or perceived, in answering the UN’s call for help. Help we are able to provide.

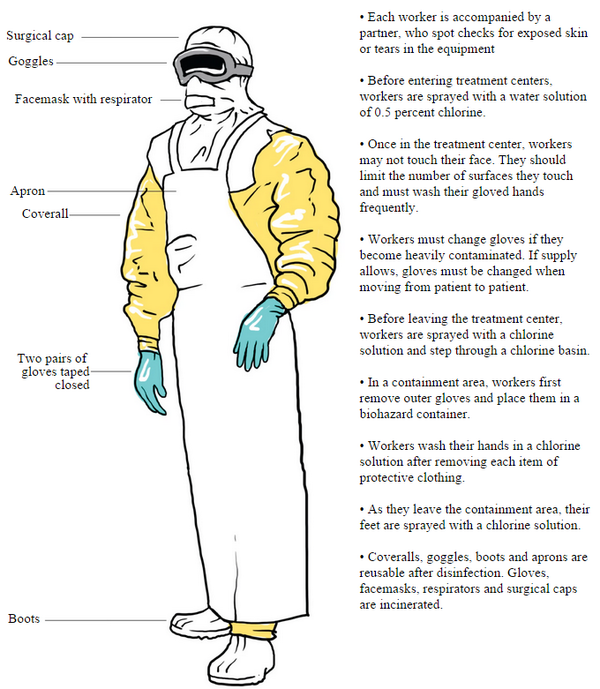

It would be difficult, heartbreaking, hard work. We know that Aussies are more than capable of doing that. In fact, the more people on the ground, helping, the easier the burden would be. There may be some problems, and it would be naive to expect otherwise. That is why the UN has called for help. If there were no risk, and everything was simple and easy, this situation would not exist in the first place. Should a healthcare worker fall ill, there is a high chance they would die. A tragedy for their family, friends and workmates. And let’s be real, there are more risks to healthcare workers than just Ebola virus disease in these countries. There are scared and sometimes violent villagers, as well as plenty of other diseases like malaria to contend with.

The lucky country.

Australians have the wealth, the innovation, the ability, the equipment and the skills in our excellent health care workers, engineers, keepers of the peace and logistical organisers. We have the willing volunteers.

How much of our global village has to burn down before we do more than buy a bucket? Why must we focus on security threats, economic impact, terrorism and political stability when it is the humanitarian aspects that should our priority? Yes, this seems to be the only way to communicate with politicians. But is the way forward for us as a nation that something has to be become a direct threat to us and our lucky country way of life before we lend a hand? Is that who we want to be? Can we not expect a more human perspective from our leaders and ourselves? We think we can.

References

- http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2014/ebola-20140808/en/

- http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/sep/29/australia-cannot-bring-health-workers-home-from-african-ebola-zones

- http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2014/09/very-few-aircraft-equipped-evacuate-ebola-patients

- http://www.news.com.au/national/medecins-sans-frontieres-slams-australias-ebola-response/story-fncynjr2-1227061379772

- http://www.pm.gov.au/media/2014-09-25/address-united-nations-general-assembly-united-nations-new-york

- http://www.unmultimedia.org/radio/english/2014/09/one-billion-dollars-needed-to-contain-ebola-outbreak/#.VCv3i_na6-0